Landslide; a ghost story

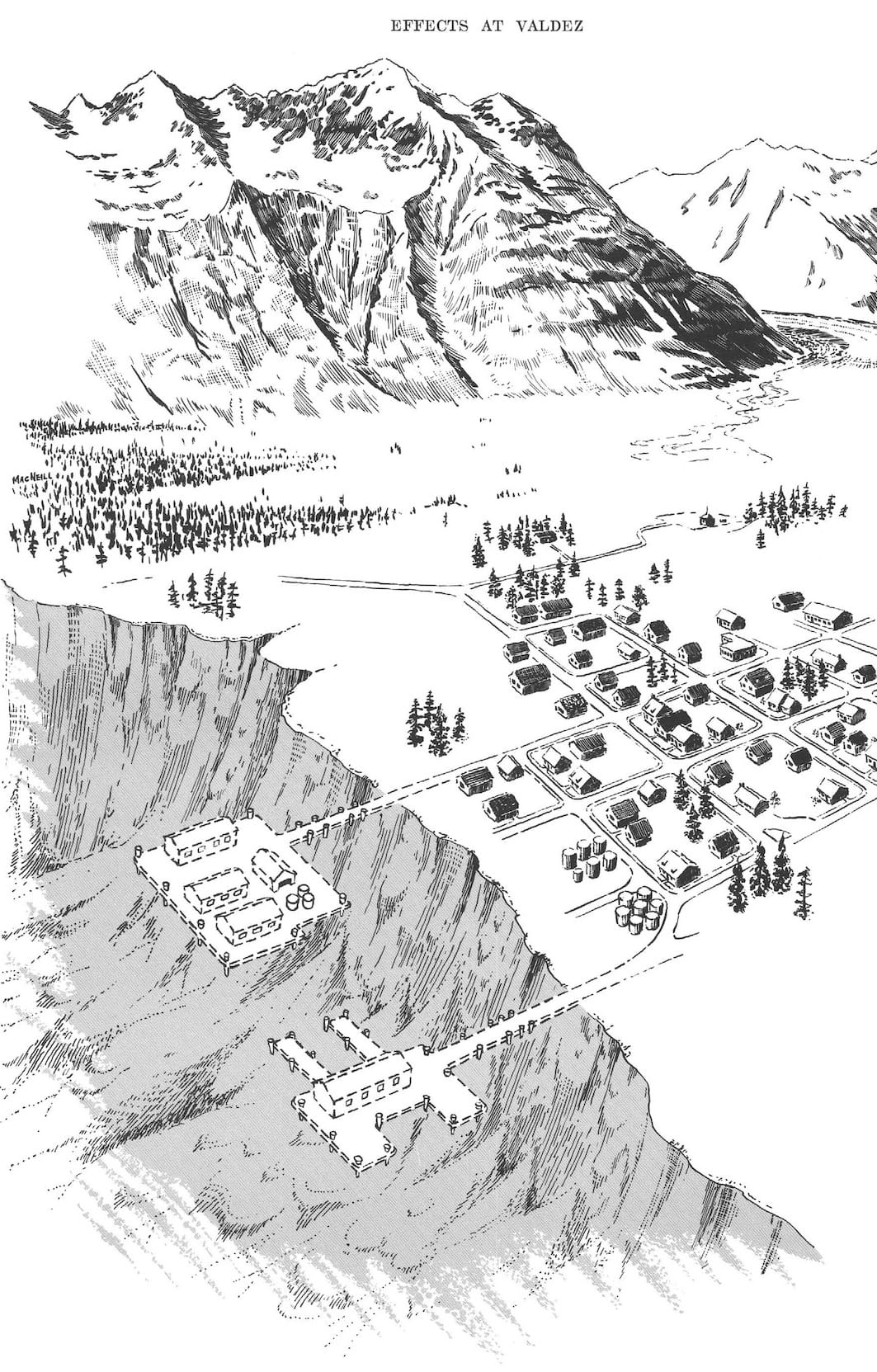

On March 27, 1964, a converted liberty ship named the SS Chena brought a shipment of supplies to the port of Valdez, Alaska. Valdez, which I need you to know is pronounced “valDEEZ,” sits at the end of a fjord-a narrow inlet carved by a glacier. The town accreted there, more than being carefully sited and built, mostly as a result of a massive gold-rush scam . It’s the northernmost ice-free deepwater port in the US, which makes it important, but it’s a tiny town: in 1964, only about 1,200 people lived there. When the Chena arrived for its regular supply delivery, people gathered at the dock to watch it, and to catch the candy and oranges the crew always tossed out to the kids. A little while later, about 15 miles underground and 40 miles away, the pressure that had built up along the Aleutian subduction zone erupted, letting the Pacific tectonic plate shove a little further under the continental North American plate. The resulting megathrust earthquake was a 9.2 in magnitude-the second-strongest recorded on Earth. It reshaped the science of seismology and provided new evidence for the then-tentative theory of plate tectonics. More immediately, it caused parts of the Alaskan coast to rise nearly forty feet, dropped others below sea level, triggered enormous tsunamis, and rang the planet like a bell . Most of the territory affected by the quake is barely populated, but a hundred and thirty-nine people died, most of them in local and distant tsunamis. Down the Oregon Coast from where I live, four children and a family dog camping on the beach with their family were swept out to sea and drowned. Much of Crescent City, California was destroyed. Tivers sloshed as far away as Texas and Louisiana. Something else happened in Valdez. The town was built on glacial moraine , a silty deposit of disorganized debris left behind by the ploughing march of a glacier. Near the shoreline, this jumble of unconsolidated rock and sand went down for 600 feet. And the ground was very, very wet. The water table was only a few feet below the surface of the town, and in late March of 1964, between that barely-subterranean water and the melt from Valdez’s extraordinarily heavy snows, the ground was as sodden as soil gets. Under normal conditions, even wet, disorganized soil will hold up things like buildings and people because the contact forces between solid particles let them transfer weight down into bedrock or denser soil below. But we know now-in part because of what geologists learned from the ‘64 earthquake-that when strong, sudden shocks hit loose, saturated soil, they can compress the water that fills the gaps between all those loose particles. When the shock is strong enough, the water pressure exceeds the forces holding the solid particles together and the water just...wins. The soil stops behaving like a solid and liquefies , and this happens all at once. Buried things like sewer pipes rise up and erupt through...

Preview: ~500 words

Continue reading at Murmel

Read Full Article