How Hannah Arendt can help us understand this new age of far-right populism

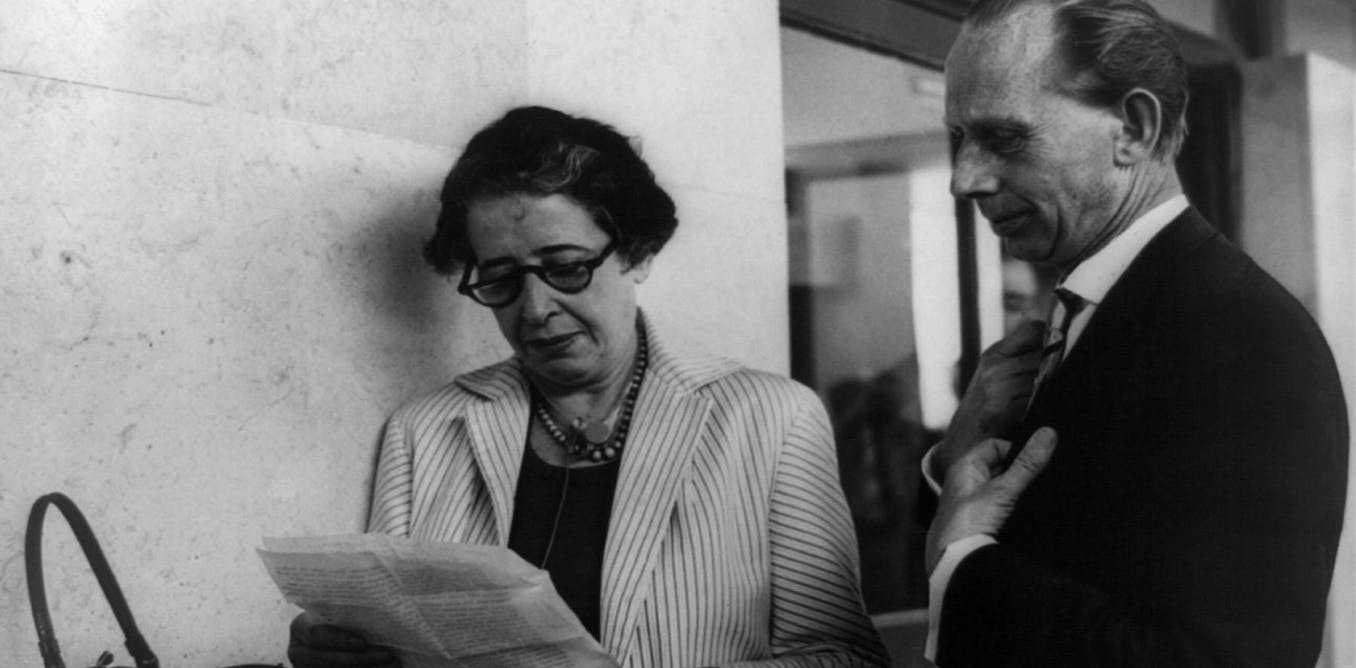

Sales of Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) rocketed when Donald Trump won the 2016 US presidential election. Nearly a year into the second Trump administration - and 50 years since Arendt’s death in December 1975 - it seems like an apposite time to revisit the book and see what light it sheds on 2025. Penguin Arendt in 1930, at the age of 24.Granger Historical Pictorial Archive / Alamy Donald Trump’s politics have helped foster right-wing populism in the US.Joshua Sukoff / Shutterstock The book is brilliant but difficult, combining history, political science and philosophy in a way that can be very disorientating. So what might we, as democratic citizens, gain from reading it? Born to a secular German Jewish family in 1906, Arendt studied philosophy under Martin Heidegger and Karl Jaspers before turning to Zionist activism in Berlin in the early 1930s. After a brush with the gestapo, she fled to France, and in 1941 left Europe for the US. So when she began researching Origins in the early 1940s, she was no stranger to totalitarianism . Penguin Totalitarianism, she argued, was a radically new form of government distinguished by its ideological conception of history. For the Nazis, history was a clash of races; for Stalinism , it was class war. Either way, totalitarian leaders sought to execute historical “laws” by forcibly reshaping the humans they ruled. Humanity, Arendt said, is distinguished by its infinite variability - no person can ever entirely substitute for another. Totalitarianism aimed to destroy this. It isolated individuals, dissolving the bonds through which they unite and empower each other, and sought to extinguish human personhood. The concentration camps’ total domination did so by reducing each inmate to “a bundle of reactions that can be liquidated and replaced” before killing them. With everyone ultimately subject to this threat, totalitarianism rendered the human person as such, superfluous. Rather than pursuing stability, totalitarianism was always a movement, constantly instigating change. When its propaganda collided with facts, it brutalised reality until the facts conformed. Its ideal subjects not only believed its lies: they no longer found the distinction between truth and falsehood meaningful. This was “post-truth politics” at its most extreme. Common sense won’t save us Comparing today’s politics to fully fledged totalitarianism can be illuminating . But if it’s all we do, we risk overlooking Arendt’s subtler lessons about warning signs that can help us gauge threats to democracy. The first is that political catastrophe isn’t always signposted by great causes, but arises when sometimes seemingly trivial developments converge. The greatest example for Arendt was political antisemitism. During the 19th century, only a “crackpot” fringe embraced it. By the 1930s, it was driving world politics. This resonates with hard-right and far-right ideology today. Ideas widely seen as eccentric 20 years ago have increasingly come to shape democratic politics. Anti-immigrant sentiment and xenophobia penetrate the political mainstream. Alongside growing Islamophobia, antisemitism is on the rise again too. Granger Historical Pictorial Archive / Alamy The mainstreaming of previously...

Preview: ~500 words

Continue reading at Murmel

Read Full Article